High-tech collecting as a hobby is a relatively recent one, and it came about when people realized that vintage computer memorabilia was being thrown away. Collectors are a varied lot, including the casual CPU keychain collector, those who buy and save computer case stickers, and even those who buy, preserve, and restore entire vintage computer systems. An extreme example of this is the Cray Y-MP C90 supercomputer listed on eBay in September 2000; it sold to a private individual for $45,000, down from the original list price of $35 million.

Who are these people? They represent all walks of life, from the guy down the street who collects old video game systems to tech industry leaders who want to preserve the history of computing hardware and software. These articles below describe the ordeals and successes of people who buy, sell & collect this vanished technology:

Rare 1980's Apple Computer plush bear gift goes up for auction

Rare Apple Computer plush bear collectible at auction (2021)

The UK, April 29, 2021

Vectis Auctions will present for sale a unique piece of Apple computing history which has a pre-sale estimate of £800 - £1200.

The beige plush bear was the prototype created by Clara Toys for a small number of bears destined to be gifted to a small by a senior group of Directors from Apple HQ in California. The gift was to commemorate the visit to the first Apple facility built outside of the US in 1980.

Robert Haire, the then General Manager of Apple in Ireland, approached a local toy company based on the same street (Millstreet), to produce a souvenir gift. This 21" / 53cm, fawn, synthetic plush bear proudly sported the iconic Apple Computers rainbow logo to his chest.

The logo used for the bruin was the second one the company used; the first, short lived one was seen to be too complicated. Co-Founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniac felt it old fashioned and once Wayne departed, aimed for a more modern logo. Graphic designer Rob Janoff was tasked with the job and created the now iconic bitten apple design in 1977, the missing section a pun on bite /byte. To him it also represented the fruit of creation in its simplest form. The addition of the rainbow's colors reflected the new revolutionary addition to the Apple range – the Apple II, having the world's first color display monitor.

It is probably a unique piece from the period as use of the apple logo was fiercely guarded by the company. Today, early Apple collectables are now keenly sought after, even the mass produced and sold badges and jewelry fetching a premium. Interest has been increasing for vintage computer items. In 2013 an Apple 1 sold for £390,000 and a year later a similar model fetched $905,000 at auction.

Specialist Kathy Taylor said ""We're really excited to be selling this unique piece of Apple computing history and am sure he would make a talking point for any computer collector".

The unique, prototype ted was being sold on Thursday 29th April at Vectis Auctions by the family of Apple General Manager Robert Haire having a pre-sale estimate of £800 - £1200.

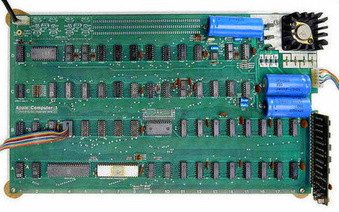

Apple 1 Computer sells for $905,000 at Auction

Apple 1 Computer (1976)

Oct 22, 2014, Reuters

One of the few remaining examples of Apple Inc's first pre-assembled computer, Apple-1, sold for $905,000 at an auction in New York on Wednesday, far outstripping expectations.

The relic, which sparked a revolution in home computing, is thought to be one of the first batch of 50 Apple-1 machines assembled by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak in Steve Job's family garage in Los Altos, California in the summer of 1976.

Auction house Bonhams had said it expected to sell the machine, which was working as of September, for between $300,000 and $500,000.

The buyer was The Henry Ford organization, which plans to display the computer in its museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

"The Apple-1 was not only innovative, but it is a key artifact in the foundation of the digital revolution," Henry Ford President Patricia Mooradian said in a statement.

There were few buyers for the first Apples until Paul Terrell, owner of electronics retailer Byte Shop, placed an order for 50 and sold them for $666.66 each.

After that initial success, Jobs and Wozniak produced another 150 and sold them to friends and other vendors.

Previously, a working Apple-I was sold by Sotheby's auction house in 2012 for $374,500.

Fewer than 50 original Apple-1s are believed to survive.

One of the few remaining examples of Apple Inc's first pre-assembled computer, Apple-1, sold for $905,000 at an auction in New York on Wednesday, far outstripping expectations.

The relic, which sparked a revolution in home computing, is thought to be one of the first batch of 50 Apple-1 machines assembled by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak in Steve Job's family garage in Los Altos, California in the summer of 1976.

Auction house Bonhams had said it expected to sell the machine, which was working as of September, for between $300,000 and $500,000.

The buyer was The Henry Ford organization, which plans to display the computer in its museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

"The Apple-1 was not only innovative, but it is a key artifact in the foundation of the digital revolution," Henry Ford President Patricia Mooradian said in a statement.

There were few buyers for the first Apples until Paul Terrell, owner of electronics retailer Byte Shop, placed an order for 50 and sold them for $666.66 each.

After that initial success, Jobs and Wozniak produced another 150 and sold them to friends and other vendors.

Previously, a working Apple-I was sold by Sotheby's auction house in 2012 for $374,500.

Fewer than 50 original Apple-1s are believed to survive.

You Can't Eat These Chips, But Some Find Silicon Addictive

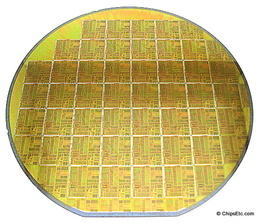

Intel Wafer w/ Pentium Processor Chips (1993)

Aug 27, 2014, Dow Jones Business News

WELLINGTON, Nev. - From his basement in a sparsely populated part of northwestern Nevada, Patrick Mulreany operates a museum that attracts about four visitors a year. Its focus: semiconductors and the shiny disks used to make them.

The former Hewlett-Packard Co. engineer's private collection of about 120 displays highlights advancements in the electronics industry. It also points to the peculiarities of a small number of people whose passion is silicon platters.

"There's a lot of stuff around here that's one of a kind," said Mr. Mulreany, smiling as he led a visitor down a long hall with dozens of framed displays of chips and wafers on the walls.

Stamp or coin collectors can usually point to the artistic characteristics of their holdings. Not people who seek out semiconductor wafers, which are processed in factories and diced up to yield individual chips.

Though wafers are largely indistinguishable from one another to the untrained eye, collectors see aesthetic merit.

"If you hold them in the sunshine, they just spit rainbows right back at your face. They're beautiful," says Joyce Haughey, a graphics designer from Trafalgar, Ind., who keeps several thousand scrap wafers in her studio.

Some enthusiasts, like Timothy Sears of Huntsville, Ala., use microscopes to view the industrial artistry inside chips. "Like futuristic cities with roads and buildings, hundreds of millions of components are connected in vast landscapes only visible at ultrahigh magnifications," he says.

But motivations vary widely among wafer lovers, a tiny tribe who have never been reliably counted and don't typically engage in organized activities.

Ms. Haughey, for example, turns electronic components into works of art. Others assemble displays based on technical or historical significance. Still others seek profit by finding unusual wafers or chips and reselling them.

Wafers, created by slicing up silicon ingots, are processed using costly machines that trace complex circuit patterns and selectively add and remove silicon and other materials. To yield more chips per batch, manufacturers have increased wafer diameters over the years from an inch or two to 12 inches in some cases.

Collecting them can take effort, since wafers are an interim manufacturing step rather than a product companies sell. Those deemed not suitable for commercial purposes--if not recycled by manufacturers--may wind up as gifts to employees or partners, in scrap heaps or funneled to flea markets or websites like eBay.

Collectors typically seek out processed wafers, which give off an iridescence when light strikes them at certain angles.

Visual effects draw people like Antoine Bercovici, a postdoctoral researcher from Paris who collaborates with a friend to take colorful microphotographs of the inside of chips.

A microscope can sometimes uncover surprises, Mr. Bercovici notes. One H-P chip from the 1990s, code-named " Hummingbird," includes a picture of that bird that is revealed under heavy magnification. It's a kind of inside joke, a decoration few will ever see. Another, dubbed "Velociraptor," sports a tiny image of the dinosaur. Many such images end up in "Silicon Zoo," an online gallery run by Michael W. Davidson, a Florida State University researcher and photographer.

Wafers don't always give up their secrets easily. Many are unmarked by manufacturers or have logos or numbers that aren't easy to interpret.

Steve Tinter, a collector in Sydney, Australia, says he sometimes spends hours studying wafers under a microscope to identify chips and their manufacturers. His holdings of more than 1,000 wafers include rarities like creations of former supercomputer maker nCube Corp. and many unidentified wafers from Xerox Corp. "I have no idea what they are even after trying to find out for more than a year," he says.

Steve Emery, a collector from Winter Park, Fla., who owns about 20,000 wafers in complete or partial form, says he spent many hours over a five-year period figuring out the provenance of one wafer.

Most wafers aren't worth much, but some finds can pay off. Those with aesthetic appeal are often listed on eBay for $10 to $20 each. Historically significant chips can fetch thousands of dollars. Mr. Tinter, who says he sells wafers sometimes to "feed the addiction" to buying and selling recently placed a $1,000 price on eBay for a wafer featuring Motorola 68000 chips--a variety used in computers like Apple Inc.'s Lisa, from the early 1980s.

Mr. Emery says he can quickly flick through such online listings and identify chips and when wafers were fabricated and judge whether a purchase of $15 to $20 might be worth hundreds. "There's definitely a high when you hit it," he says.

He estimates that one tiny wafer sporting chips from industry pioneer Fairchild Semiconductor, which probably cost him $20, is now worth $5,000 to $10,000. On the other hand, Mr. Emery says he bought about 4,000 wafers for roughly $ 600, an average cost of around 15 cents each.

Collectors do more than search through eBay. One person who buys and sells wafers speaks of meeting factory workers years ago in cars at remote quiet locations, receiving disks wrapped in work gloves. "Some of the guys that did supply to me got in trouble [with their employers] and were probably fired" for taking company property, says Bob Lewis, a Sunnyvale, Calif., resident who has been gathering and selling silicon wafers for more than three decades.

Ms. Haughey once drove 85 miles to gather a 900-pound box of scrap wafers, and then spent about a month sifting through it. "It was cold, it was Christmas," she recalls. The wafers were "out in the shed, and to get to the bottom of the box I was like almost standing on my head leaning in."

While they don't gather formally, some collectors stay in touch to trade wafers and share experiences. Others have more specific reasons for connecting.

Mr. Emery, for example, assembles what he calls "chipscapes"--displays showcasing various historical semiconductors. He has sold hundreds of them to buyers around the globe, including museums. One client is Mr. Mulreany, who bought about 90 displays for his private collection before starting to design his own, sometimes supplemented by Mr. Emery's artwork.

The collection is one of Mr. Mulreany's many hobbies. He is also a ham radio operator and electronics tinkerer. He spent 34 years working on a 1,920-page tome on standard verbs in the Irish language. He is open to the idea of letting the public see his semiconductor collection someday, but he seems satisfied to operate a silicon museum that attracts a very small audience.

"I spend a lot of time by myself," he says. "I don't really need friends, I guess."

WELLINGTON, Nev. - From his basement in a sparsely populated part of northwestern Nevada, Patrick Mulreany operates a museum that attracts about four visitors a year. Its focus: semiconductors and the shiny disks used to make them.

The former Hewlett-Packard Co. engineer's private collection of about 120 displays highlights advancements in the electronics industry. It also points to the peculiarities of a small number of people whose passion is silicon platters.

"There's a lot of stuff around here that's one of a kind," said Mr. Mulreany, smiling as he led a visitor down a long hall with dozens of framed displays of chips and wafers on the walls.

Stamp or coin collectors can usually point to the artistic characteristics of their holdings. Not people who seek out semiconductor wafers, which are processed in factories and diced up to yield individual chips.

Though wafers are largely indistinguishable from one another to the untrained eye, collectors see aesthetic merit.

"If you hold them in the sunshine, they just spit rainbows right back at your face. They're beautiful," says Joyce Haughey, a graphics designer from Trafalgar, Ind., who keeps several thousand scrap wafers in her studio.

Some enthusiasts, like Timothy Sears of Huntsville, Ala., use microscopes to view the industrial artistry inside chips. "Like futuristic cities with roads and buildings, hundreds of millions of components are connected in vast landscapes only visible at ultrahigh magnifications," he says.

But motivations vary widely among wafer lovers, a tiny tribe who have never been reliably counted and don't typically engage in organized activities.

Ms. Haughey, for example, turns electronic components into works of art. Others assemble displays based on technical or historical significance. Still others seek profit by finding unusual wafers or chips and reselling them.

Wafers, created by slicing up silicon ingots, are processed using costly machines that trace complex circuit patterns and selectively add and remove silicon and other materials. To yield more chips per batch, manufacturers have increased wafer diameters over the years from an inch or two to 12 inches in some cases.

Collecting them can take effort, since wafers are an interim manufacturing step rather than a product companies sell. Those deemed not suitable for commercial purposes--if not recycled by manufacturers--may wind up as gifts to employees or partners, in scrap heaps or funneled to flea markets or websites like eBay.

Collectors typically seek out processed wafers, which give off an iridescence when light strikes them at certain angles.

Visual effects draw people like Antoine Bercovici, a postdoctoral researcher from Paris who collaborates with a friend to take colorful microphotographs of the inside of chips.

A microscope can sometimes uncover surprises, Mr. Bercovici notes. One H-P chip from the 1990s, code-named " Hummingbird," includes a picture of that bird that is revealed under heavy magnification. It's a kind of inside joke, a decoration few will ever see. Another, dubbed "Velociraptor," sports a tiny image of the dinosaur. Many such images end up in "Silicon Zoo," an online gallery run by Michael W. Davidson, a Florida State University researcher and photographer.

Wafers don't always give up their secrets easily. Many are unmarked by manufacturers or have logos or numbers that aren't easy to interpret.

Steve Tinter, a collector in Sydney, Australia, says he sometimes spends hours studying wafers under a microscope to identify chips and their manufacturers. His holdings of more than 1,000 wafers include rarities like creations of former supercomputer maker nCube Corp. and many unidentified wafers from Xerox Corp. "I have no idea what they are even after trying to find out for more than a year," he says.

Steve Emery, a collector from Winter Park, Fla., who owns about 20,000 wafers in complete or partial form, says he spent many hours over a five-year period figuring out the provenance of one wafer.

Most wafers aren't worth much, but some finds can pay off. Those with aesthetic appeal are often listed on eBay for $10 to $20 each. Historically significant chips can fetch thousands of dollars. Mr. Tinter, who says he sells wafers sometimes to "feed the addiction" to buying and selling recently placed a $1,000 price on eBay for a wafer featuring Motorola 68000 chips--a variety used in computers like Apple Inc.'s Lisa, from the early 1980s.

Mr. Emery says he can quickly flick through such online listings and identify chips and when wafers were fabricated and judge whether a purchase of $15 to $20 might be worth hundreds. "There's definitely a high when you hit it," he says.

He estimates that one tiny wafer sporting chips from industry pioneer Fairchild Semiconductor, which probably cost him $20, is now worth $5,000 to $10,000. On the other hand, Mr. Emery says he bought about 4,000 wafers for roughly $ 600, an average cost of around 15 cents each.

Collectors do more than search through eBay. One person who buys and sells wafers speaks of meeting factory workers years ago in cars at remote quiet locations, receiving disks wrapped in work gloves. "Some of the guys that did supply to me got in trouble [with their employers] and were probably fired" for taking company property, says Bob Lewis, a Sunnyvale, Calif., resident who has been gathering and selling silicon wafers for more than three decades.

Ms. Haughey once drove 85 miles to gather a 900-pound box of scrap wafers, and then spent about a month sifting through it. "It was cold, it was Christmas," she recalls. The wafers were "out in the shed, and to get to the bottom of the box I was like almost standing on my head leaning in."

While they don't gather formally, some collectors stay in touch to trade wafers and share experiences. Others have more specific reasons for connecting.

Mr. Emery, for example, assembles what he calls "chipscapes"--displays showcasing various historical semiconductors. He has sold hundreds of them to buyers around the globe, including museums. One client is Mr. Mulreany, who bought about 90 displays for his private collection before starting to design his own, sometimes supplemented by Mr. Emery's artwork.

The collection is one of Mr. Mulreany's many hobbies. He is also a ham radio operator and electronics tinkerer. He spent 34 years working on a 1,920-page tome on standard verbs in the Irish language. He is open to the idea of letting the public see his semiconductor collection someday, but he seems satisfied to operate a silicon museum that attracts a very small audience.

"I spend a lot of time by myself," he says. "I don't really need friends, I guess."

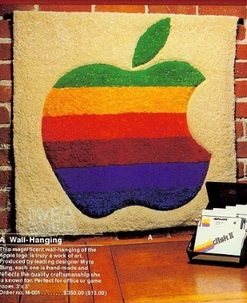

Rare Myra Burg Apple Computer Rainbow Logo

Wall Hanging Sells at Auction

July 13th 2012, iphonesavior.com

In 1983, Steve Jobs commissioned artist Myra Burg to hand-craft 25 Apple rainbow logo wall-hangings for the company's gift catalog. In a recent interview with Ms. Burg — I discovered that she actually produced 27 of those limited edition works of art. Twenty five were listed in Apple's catalog for $350 each — Myra then made an additional one as a gift for Steve Jobs and another one for Steve Wozniak.

New York native Donald Metzger, who worked for two years as a Tony Soprano photo-double for James Gandolfini in the epic HBO TV series The Sopranos, just happens to own one of those rare original Apple wall-hangings and he's putting it up for sale.

While it's unclear if Steve Wozniak still owns his piece, the wall-hanging made for Jobs was left behind in his Woodside mansion — as documented in a photo I spotted about a month before the home was demolished last year.

When Metzger recently contacted Myra Burg about his Apple art, he had no clue that his signed wall-hanging was a limited edition. Until Metzger located Burg through her online gallery, he believed the piece was some mass-produced item shipped out to Apple resellers back in 1983.

"I decided to put a feeler out there to see what it might be worth," said Metzger about the wall-hanging. "I saw Myra Burg's name on the piece so I did a Google search and I called her up."

"She flipped out! I had no idea there were only 27 of these — my mind was blown right out of the sockets. I thought Apple had sent these out to all their dealers in 1983."

Mr. Metzger worked at a computer store in Manhattan when the rug first arrived inside a plain cardboard box almost 30 years ago. He has worked in the PC business since 1980, but it was his uncanny resemblance to James Gandolfini that landed him work on The Sopranos for the final two seasons of the show, after winning a Sopranos look-alike contest hosted by HBO. "My work on the show was primarily doing the driving scenes where you’d see Tony’s Cadillac Escalade going by the screen quickly enough where you wouldn’t have seen him close-up." said Metzger.

"The first episode of the final season I was in all of the driving scenes around Greenwood Lake, New York," Metzger added. "There were other episodes where Tony was a passenger, like in Christopher Moltisanti's SUV just before the roll over accident when he met his demise.”

But before Metzger found his touch of fame as a Tony Soprano look-alike, he worked as a computer consultant specializing in data base applications. It was that same work which placed him at the center of the gruesome aftermath following New York's 9/11 tragedy.

"The day after 9/11, I was hired as part of the World Trade Center Disaster team at the New York City Medical Examiner's Office as co-designer and developer of the computer system used to cataloge over 20,000 bodies and body parts recovered from the World Trade Center site."

"I worked for three years on that system which included the Remains inventory, identification tracking, the Reported Missing list, DNA identification and generation of the daily up to date causality numbers furnished to the media." Don added.

Thanks to Donald Metzger, the fantastical tale surrounding Apple's branded wall-hanging that began for me late last year when I first reached out to Myra Burg, has become an even more bizarre story by several leaps and bounds. Not only does Don still own an iconic piece of original Apple art, it's been kept in beautiful condition — looking like it just dropped out of Apple's 1983 gift catalog two weeks ago

I consider this collectible piece of Apple history to be priceless, but Don Metzger hopes to sell it for a price that even Tony Soprano might consider a bit hefty. Let's just say that any offer south of twenty large ($20k) won't command Don's attention.

"I'd really rather not sell it," says Metzger, "But I'm willing to listen if someone makes me an offer I can’t refuse."

In 1983, Steve Jobs commissioned artist Myra Burg to hand-craft 25 Apple rainbow logo wall-hangings for the company's gift catalog. In a recent interview with Ms. Burg — I discovered that she actually produced 27 of those limited edition works of art. Twenty five were listed in Apple's catalog for $350 each — Myra then made an additional one as a gift for Steve Jobs and another one for Steve Wozniak.

New York native Donald Metzger, who worked for two years as a Tony Soprano photo-double for James Gandolfini in the epic HBO TV series The Sopranos, just happens to own one of those rare original Apple wall-hangings and he's putting it up for sale.

While it's unclear if Steve Wozniak still owns his piece, the wall-hanging made for Jobs was left behind in his Woodside mansion — as documented in a photo I spotted about a month before the home was demolished last year.

When Metzger recently contacted Myra Burg about his Apple art, he had no clue that his signed wall-hanging was a limited edition. Until Metzger located Burg through her online gallery, he believed the piece was some mass-produced item shipped out to Apple resellers back in 1983.

"I decided to put a feeler out there to see what it might be worth," said Metzger about the wall-hanging. "I saw Myra Burg's name on the piece so I did a Google search and I called her up."

"She flipped out! I had no idea there were only 27 of these — my mind was blown right out of the sockets. I thought Apple had sent these out to all their dealers in 1983."

Mr. Metzger worked at a computer store in Manhattan when the rug first arrived inside a plain cardboard box almost 30 years ago. He has worked in the PC business since 1980, but it was his uncanny resemblance to James Gandolfini that landed him work on The Sopranos for the final two seasons of the show, after winning a Sopranos look-alike contest hosted by HBO. "My work on the show was primarily doing the driving scenes where you’d see Tony’s Cadillac Escalade going by the screen quickly enough where you wouldn’t have seen him close-up." said Metzger.

"The first episode of the final season I was in all of the driving scenes around Greenwood Lake, New York," Metzger added. "There were other episodes where Tony was a passenger, like in Christopher Moltisanti's SUV just before the roll over accident when he met his demise.”

But before Metzger found his touch of fame as a Tony Soprano look-alike, he worked as a computer consultant specializing in data base applications. It was that same work which placed him at the center of the gruesome aftermath following New York's 9/11 tragedy.

"The day after 9/11, I was hired as part of the World Trade Center Disaster team at the New York City Medical Examiner's Office as co-designer and developer of the computer system used to cataloge over 20,000 bodies and body parts recovered from the World Trade Center site."

"I worked for three years on that system which included the Remains inventory, identification tracking, the Reported Missing list, DNA identification and generation of the daily up to date causality numbers furnished to the media." Don added.

Thanks to Donald Metzger, the fantastical tale surrounding Apple's branded wall-hanging that began for me late last year when I first reached out to Myra Burg, has become an even more bizarre story by several leaps and bounds. Not only does Don still own an iconic piece of original Apple art, it's been kept in beautiful condition — looking like it just dropped out of Apple's 1983 gift catalog two weeks ago

I consider this collectible piece of Apple history to be priceless, but Don Metzger hopes to sell it for a price that even Tony Soprano might consider a bit hefty. Let's just say that any offer south of twenty large ($20k) won't command Don's attention.

"I'd really rather not sell it," says Metzger, "But I'm willing to listen if someone makes me an offer I can’t refuse."

Moscow Apple Museum Steve Jobs Tribute (2011)

Apple Computer Memorabilia

Huffingtonpost.com, October 7, 2011

Andrei Antonov, who has been collecting rare Apple memorabilia for the last three decades, is now publicly floating the idea of creating an Apple Museum in Moscow.

The Moscow printer's collection of rare Apple computer products may become a public tribute to Steve Jobs' life work and the inventiveness of the corporation he founded with dance-aficiando Steve Wozniak.

Antonov told the BBC that he wanted to mark the achievements of Jobs and the company he started by showing how Apple's first products, the computing equivalent of hand axes, gradually evolved to become the ubiquitous iPhones of today.

Antonov's collection includes a computer designed for astronauts, early laptops, rare gaming gadgets from the '90s and all manner of disk drives. The museum will no doubt be perfect for anyone with iMac nostalgia. In the meantime, Apple fans can head to the garage where it all began.

(Among the items in this Apple memorabilia collection are a rare working example of a late-1970s Apple II, and a Mac Portable - a model that US astronauts took into space)

Andrei Antonov, who has been collecting rare Apple memorabilia for the last three decades, is now publicly floating the idea of creating an Apple Museum in Moscow.

The Moscow printer's collection of rare Apple computer products may become a public tribute to Steve Jobs' life work and the inventiveness of the corporation he founded with dance-aficiando Steve Wozniak.

Antonov told the BBC that he wanted to mark the achievements of Jobs and the company he started by showing how Apple's first products, the computing equivalent of hand axes, gradually evolved to become the ubiquitous iPhones of today.

Antonov's collection includes a computer designed for astronauts, early laptops, rare gaming gadgets from the '90s and all manner of disk drives. The museum will no doubt be perfect for anyone with iMac nostalgia. In the meantime, Apple fans can head to the garage where it all began.

(Among the items in this Apple memorabilia collection are a rare working example of a late-1970s Apple II, and a Mac Portable - a model that US astronauts took into space)

Collectors loath to say goodbye, old chips (2005)

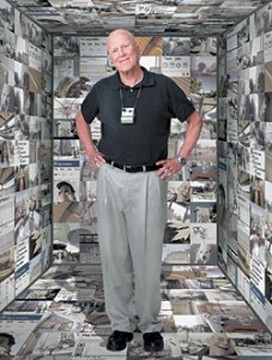

Steve Emery

By Dean Takahashi, San Jose Mercury News, Sept. 19, 2005

Collectors keep a piece of Silicon Valley heritage alive

David Pienknagura recently paid $350 for an Intel microprocessor, and he's not even sure if it works. Whether he got a bargain depends on your perspective.

He bought the computer chip -- the Intel 4004, the first microprocessor the company debuted in 1971 -- on eBay from another collector. Pienknagura, a Palo Alto programmer, could have used that money to buy Intel's current chip, a Pentium 4 microprocessor that runs at 3.2 gigahertz vs. the older chip's 108 kilohertz. If he did, he would have gotten approximately 1 million times more

processing power. For that matter, he could have bought a complete personal computer with a display, for roughly the same amount. But Pienknagura is that rare breed of collector who buys these chips for the love of technology and its history. And apparently he's not alone. He finds these particular chips for sale on eBay every couple of weeks or so, and on Web sites dedicated to collectors. Prices on some recent 4004 chip auctions have ranged from $212 to $520. Each 4004 chip for sale on eBay generates about 15 bids, including some from Japan, South Korea, Germany, Australia and Britain. ``It's a worldwide phenomenon,'' he said.

One of his comrade collectors is Gennadiy Shvets, a 40-year-old programmer in Fairfax, Va. He runs a vintage chip collector's Web site, cpu-world.com. Shvets said he gets several thousand visitors a day to his Web site, and they're interested in all sorts of chips, not just the original one from Intel. Like Pienknagura, Shvets started his hobby a few years ago because he wanted to hang some old chips in a frame on a wall in his home. It turned into a big hobby, and now he has cabinets full of chips. Shvets said he doesn't want his wife to know just how much he spends on old chips. But he notes his collection of more than 100 different families of chips -- including some vintage Intel 4004 chips -- is worth about $10,000.

He is trying to put a photo of every single chip on his Web site, complete with information about its origins and uses. He has his own tester to check to see if the chips can still function, but at this point he has no plans to put together a working computer with old chips. ``If someone tells me a number or shows me a photo, I can tell them about the chip, when it was made and other things about it,''he said. Like most collectors, Shvets is more interested in buying than trading. His site includes a list of chips that he wants, including any microprocessor from Rise Technology, a San Jose company that went out of business after trying to take on Intel.

George Phillips Jr., a programmer who collects chips in Columbia, S.C., started collecting a few years ago when he stumbled on rare chips for sale on eBay. He discovered that many chips are now rare because they were melted down to recycle their gold wiring. And some chips, like the Intel 8080 microprocessor, which came after the 4004, are rare because they were quickly replaced by new versions that were slightly different. Now he has 1,000 chips.

1,300-page guide:

`These chips, in addition to changing the way we live, represent the work of many of the most brilliant engineers of the last century,'' said Phillips, who took five years to write a 1,300-page guide to collecting vintage Intel chips. ``It would be a shame if it's all lost to the smelter.'' Admittedly, it's an odd habit.

Steve Emery, a 47-year-old collector in Winter Park, Fla., considers himself a historian. He has been collecting since 1978, when a professor gave him a non-working Intel 8080A, one of the successors to the original 4004. ``My wife is just grateful that I don't collect whole computers as some do, '' said Emery, who runs the chip collector Web site chipscapes.com. ``For me it is the confluence of events, the inventor's struggles, the market challenges and ultimately the introduction of a device that changes the world that makes a chip collectible. ''

The hobby started for Pienknagura some years ago when he was cleaning his garage. He found an old box of chips and thought it would be fun to create a display that showed the progression of chips over time. The original Intel 4004 had 2,300 transistors and operated at 108 kilohertz. This year, Intel is going to produce an Itanium chip, codenamed Montecito, that will have 1.7 billion transistors and run at a few gigahertz. This obsession with chips is partly educational, partly nostalgic. Pienknagura is 47 and makes a living as a software engineer at a security firm in Santa Clara. He grew up in Quito, the capital of Ecuador, in a family of industrial entrepreneurs. The house was littered with lasers, chips, electric typewriters, Apple computers. He played around in his father's machine shop for fun, and he learned how to build things while watching the manufacture of things such as clothing buttons, metal coil springs and zippers.

He came to the United States in 1981, the same year that IBM launched its PC, to study engineering at Stanford. He became a software engineer specializing in embedded systems, or software for controlling a variety of machines.

Replicating a Busicom Pienknagura says his 4004 chip has never been used, but he's not sure if it would actually work. His dream is to one day build a replica of the original Busicom calculator that Intel built its original 4004 microprocessor for 34 years ago. If he used all original materials, Pienknagura estimates it could cost him $15,000 to $20,000 to do so.

The search for components could also take a lot of time. He would need to come up with the companion chips for the 4004 that fulfilled some functions such as memory, program storage, and input-output. On top of that, he would need older components that are equally hard to find. And he expects he would have to custom design some parts that aren't available.

"The software is probably the hardest thing to duplicate,'' he said.

A lot of people smile when they hear Pienknagura talk about his hobby, but his engineering friends usually understand.

"When I show it to kids, sometimes they have never even seen one and they don't understand what is inside their computers,'' he said. ``When you look at these old things, it really opens your eyes about what technology has done for us.''

Adds Phillips, "A thousand years from now, future generations are going to look back on this time and most of what we did will have been forgotten, but the microchip and the resulting computer revolution will go down as one of the most monumental turning points in history. "A thousand years from now, every museum will want a 4004 microprocessor on display under glass,'' he said.

Collectors keep a piece of Silicon Valley heritage alive

David Pienknagura recently paid $350 for an Intel microprocessor, and he's not even sure if it works. Whether he got a bargain depends on your perspective.

He bought the computer chip -- the Intel 4004, the first microprocessor the company debuted in 1971 -- on eBay from another collector. Pienknagura, a Palo Alto programmer, could have used that money to buy Intel's current chip, a Pentium 4 microprocessor that runs at 3.2 gigahertz vs. the older chip's 108 kilohertz. If he did, he would have gotten approximately 1 million times more

processing power. For that matter, he could have bought a complete personal computer with a display, for roughly the same amount. But Pienknagura is that rare breed of collector who buys these chips for the love of technology and its history. And apparently he's not alone. He finds these particular chips for sale on eBay every couple of weeks or so, and on Web sites dedicated to collectors. Prices on some recent 4004 chip auctions have ranged from $212 to $520. Each 4004 chip for sale on eBay generates about 15 bids, including some from Japan, South Korea, Germany, Australia and Britain. ``It's a worldwide phenomenon,'' he said.

One of his comrade collectors is Gennadiy Shvets, a 40-year-old programmer in Fairfax, Va. He runs a vintage chip collector's Web site, cpu-world.com. Shvets said he gets several thousand visitors a day to his Web site, and they're interested in all sorts of chips, not just the original one from Intel. Like Pienknagura, Shvets started his hobby a few years ago because he wanted to hang some old chips in a frame on a wall in his home. It turned into a big hobby, and now he has cabinets full of chips. Shvets said he doesn't want his wife to know just how much he spends on old chips. But he notes his collection of more than 100 different families of chips -- including some vintage Intel 4004 chips -- is worth about $10,000.

He is trying to put a photo of every single chip on his Web site, complete with information about its origins and uses. He has his own tester to check to see if the chips can still function, but at this point he has no plans to put together a working computer with old chips. ``If someone tells me a number or shows me a photo, I can tell them about the chip, when it was made and other things about it,''he said. Like most collectors, Shvets is more interested in buying than trading. His site includes a list of chips that he wants, including any microprocessor from Rise Technology, a San Jose company that went out of business after trying to take on Intel.

George Phillips Jr., a programmer who collects chips in Columbia, S.C., started collecting a few years ago when he stumbled on rare chips for sale on eBay. He discovered that many chips are now rare because they were melted down to recycle their gold wiring. And some chips, like the Intel 8080 microprocessor, which came after the 4004, are rare because they were quickly replaced by new versions that were slightly different. Now he has 1,000 chips.

1,300-page guide:

`These chips, in addition to changing the way we live, represent the work of many of the most brilliant engineers of the last century,'' said Phillips, who took five years to write a 1,300-page guide to collecting vintage Intel chips. ``It would be a shame if it's all lost to the smelter.'' Admittedly, it's an odd habit.

Steve Emery, a 47-year-old collector in Winter Park, Fla., considers himself a historian. He has been collecting since 1978, when a professor gave him a non-working Intel 8080A, one of the successors to the original 4004. ``My wife is just grateful that I don't collect whole computers as some do, '' said Emery, who runs the chip collector Web site chipscapes.com. ``For me it is the confluence of events, the inventor's struggles, the market challenges and ultimately the introduction of a device that changes the world that makes a chip collectible. ''

The hobby started for Pienknagura some years ago when he was cleaning his garage. He found an old box of chips and thought it would be fun to create a display that showed the progression of chips over time. The original Intel 4004 had 2,300 transistors and operated at 108 kilohertz. This year, Intel is going to produce an Itanium chip, codenamed Montecito, that will have 1.7 billion transistors and run at a few gigahertz. This obsession with chips is partly educational, partly nostalgic. Pienknagura is 47 and makes a living as a software engineer at a security firm in Santa Clara. He grew up in Quito, the capital of Ecuador, in a family of industrial entrepreneurs. The house was littered with lasers, chips, electric typewriters, Apple computers. He played around in his father's machine shop for fun, and he learned how to build things while watching the manufacture of things such as clothing buttons, metal coil springs and zippers.

He came to the United States in 1981, the same year that IBM launched its PC, to study engineering at Stanford. He became a software engineer specializing in embedded systems, or software for controlling a variety of machines.

Replicating a Busicom Pienknagura says his 4004 chip has never been used, but he's not sure if it would actually work. His dream is to one day build a replica of the original Busicom calculator that Intel built its original 4004 microprocessor for 34 years ago. If he used all original materials, Pienknagura estimates it could cost him $15,000 to $20,000 to do so.

The search for components could also take a lot of time. He would need to come up with the companion chips for the 4004 that fulfilled some functions such as memory, program storage, and input-output. On top of that, he would need older components that are equally hard to find. And he expects he would have to custom design some parts that aren't available.

"The software is probably the hardest thing to duplicate,'' he said.

A lot of people smile when they hear Pienknagura talk about his hobby, but his engineering friends usually understand.

"When I show it to kids, sometimes they have never even seen one and they don't understand what is inside their computers,'' he said. ``When you look at these old things, it really opens your eyes about what technology has done for us.''

Adds Phillips, "A thousand years from now, future generations are going to look back on this time and most of what we did will have been forgotten, but the microchip and the resulting computer revolution will go down as one of the most monumental turning points in history. "A thousand years from now, every museum will want a 4004 microprocessor on display under glass,'' he said.

Intel recalled a major chip in 1995 and turned them into keychains inscribed by the CEO (2018)

intel pentium chip keychain

Jan 5, 2018, Antonio Villas-Boas, BusinessInsider.com

Intel recalled a major chip in 1995 and turned them into keychains inscribed by the CEO — and the message speaks to Intel's current crisis

If Intel has a calendar that counted the time since its last disaster — at least public ones we know about — it would have counted 24 years. Back in 1994, a bug was discovered in the Pentium P5 family of chips Intel released in 1993 that would cause the chips to incorrectly calculate certain equations. Most users weren't impacted by the bug. But a New York Times Business Day article from 1994 suggested that scientists and engineers who "rely on their machines for precise calculations" had some reason for concern.

In the end, Intel recalled nearly a million of the flawed chips. But instead of trashing or recycling them, the company turned some of them into keychains that were handed out to Intel employees in 1995, according to a site that specializes in vintage chip memorabilia, Chips Etc.

You might be thinking that the keychains were designed to remind Intel employees of the errors made during the Pentium P5's development whenever they took out their car or house keys. But it wasn't quite as hard-hearted as that. Inscribed on the back of the keychain was an inspirational message from then-Intel CEO Andy Grove that read: "Bad companies are destroyed by crises; good companies survive them; great companies are improved by them."

Indeed, speaking to Tech Radar in back in 2014 – the 20th anniversary of the recall – Intel veteran Tom Waldrop said that the company "survived the crisis and was made stronger by it." He goes on to say that Intel changed the way it validated its products to catch errors.

The company had a good run since 1994, as few – if any – major chip errors were discovered. But that run came to an end in late 2017 and early 2018 when a design flaw was discovered in Intel chips released in the last few years.

The recently discovered design flaw in Intel chips appears far worse than the 1994 Pentium P5 chip's flaw, as it places the security of a huge number of devices at risk.

To be sure, Intel isn't the only chip maker affected, as other chip makers like ARM also contain the flaw.

So far, the company hasn't issued a recall for chips affected with the flaw, nor is there any indication that any chips will be turned into keychains. Instead, the company has worked with its competitors, operating system vendors, and original equipment vendors to issue software and firmware updates containing fixes for the issue.

We'll have to see if the updates — which will begin rolling out starting in the next few days — will do the trick, or whether we'll see a slew of Intel employees brandishing flashy new chip keychains with another inspirational message a couple of years from now.

Intel recalled a major chip in 1995 and turned them into keychains inscribed by the CEO — and the message speaks to Intel's current crisis

- Intel recalled the Pentium P5 chip in 1995 that produced errors for certain calculations.

- The recalled chips were turned into keychains for Intel employees.

- The keychains had an inscription from former Intel CEO Andy Grove that became the company's mantra, and also applies to Intel's current chip crisis.

If Intel has a calendar that counted the time since its last disaster — at least public ones we know about — it would have counted 24 years. Back in 1994, a bug was discovered in the Pentium P5 family of chips Intel released in 1993 that would cause the chips to incorrectly calculate certain equations. Most users weren't impacted by the bug. But a New York Times Business Day article from 1994 suggested that scientists and engineers who "rely on their machines for precise calculations" had some reason for concern.

In the end, Intel recalled nearly a million of the flawed chips. But instead of trashing or recycling them, the company turned some of them into keychains that were handed out to Intel employees in 1995, according to a site that specializes in vintage chip memorabilia, Chips Etc.

You might be thinking that the keychains were designed to remind Intel employees of the errors made during the Pentium P5's development whenever they took out their car or house keys. But it wasn't quite as hard-hearted as that. Inscribed on the back of the keychain was an inspirational message from then-Intel CEO Andy Grove that read: "Bad companies are destroyed by crises; good companies survive them; great companies are improved by them."

Indeed, speaking to Tech Radar in back in 2014 – the 20th anniversary of the recall – Intel veteran Tom Waldrop said that the company "survived the crisis and was made stronger by it." He goes on to say that Intel changed the way it validated its products to catch errors.

The company had a good run since 1994, as few – if any – major chip errors were discovered. But that run came to an end in late 2017 and early 2018 when a design flaw was discovered in Intel chips released in the last few years.

The recently discovered design flaw in Intel chips appears far worse than the 1994 Pentium P5 chip's flaw, as it places the security of a huge number of devices at risk.

To be sure, Intel isn't the only chip maker affected, as other chip makers like ARM also contain the flaw.

So far, the company hasn't issued a recall for chips affected with the flaw, nor is there any indication that any chips will be turned into keychains. Instead, the company has worked with its competitors, operating system vendors, and original equipment vendors to issue software and firmware updates containing fixes for the issue.

We'll have to see if the updates — which will begin rolling out starting in the next few days — will do the trick, or whether we'll see a slew of Intel employees brandishing flashy new chip keychains with another inspirational message a couple of years from now.

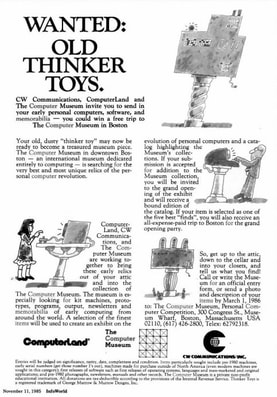

Browsing for Treasure in Trash (2006)

Lee Gallagher

Molouk Y. Ba-Isa, Arab News, ALKHOBAR, January 3, 2006

For the past year, everybody in the Kingdom has been paying a lot of attention to the rising and falling of the Saudi stock market. Unfortunately, this investment game is one in which expatriates have not been allowed to participate. But what if I told you that there was a new game in town, a sort of pot of gold scavenger hunt, and everybody was welcome to play? Would you be interested?

Last week Arab News received an e-mail from Lee Gallagher, a first sergeant in the US Army stationed in South Korea. Gallagher is a collector of Intel central processing units (CPUs). The CPU is the brains of the computer. On large machines, CPUs require one or more printed circuit boards. On personal computers and small workstations, the CPU is housed in a single chip called a microprocessor. In the last four years Gallagher has amassed one of the largest Intel CPU collections through trades and purchases worldwide — and he’s on the lookout for more.

“My collection is valued at over $500,000, but I have invested only $150,000 in assembling it,” Gallagher said. “I have several CPUs that are the only ones known in the world. I started collecting CPUs that I pulled out of old computers when I owned a little computer shop in Missouri, US. My business partner thought I was nuts and said that they were only worth the amount of gold you could get out of them, which was about $2. Then I showed him where a CPU, an Intel C4004, went for over $200 on Ebay and although he was amazed, he still didn’t get it.”

However, Gallagher really got bit by the collecting bug and he now owns 27 C4004s. He has seen these CPUs sell for over $1,000.

“Their value has more than doubled in four years and there are versions of the chip that will someday be priceless due to the very few that are out there,” Gallagher remarked.

According to Gallagher, Intel didn’t realize the potential for its chips when the company first began making CPUs. This means that Intel didn’t keep stocks of every chip made. Where are those chips now? All over the world, hidden in old computers and packed into dusty boxes of obsolete spare parts.

Since the CPU is a modern invention, it’s only in about the last decade that serious interest has been shown in collecting the older processors. There is already considerable evidence to support the potential and growing worth of early CPUs. The prices for collectible stamps, coins and baseball cards has in some cases passed millions of dollars for a single item and there is no reason to think that certain CPUs won’t someday be equally valuable.

“The one thing that was holding back interest in the hobby of collecting CPUs was that there was no collector’s guide to microchips,” said Gallagher. “In fact the Intel Corporation did a horrible job of keeping track of what they produced in the early 1970s and you can’t even find documentation on most of their computer chips even by contacting their museum.”

But that obstacle has now been overcome.

“About six years ago a computer programmer, George M. Phillips, Jr., who found the chip collecting hobby interesting, ran into this problem of not having any documentation to base his collection on,” explained Gallagher. “He decided to write an Intel Collector’s Guide. Five years later, after gathering up every Intel piece of literature he could find, he published this guide and what a resource it is. It is over 1,300 pages of information including specs, photos and the values of all the chips made in the 1970s. ‘The Collector’s Guide to Vintage Intel Microchips, 2nd Edition, 2006’ has just been released. With the publication of the guide, the hobby of collecting CPUs has been given a huge boost.”

After the release of the Guide to Vintage Intel Microchips last year, increased interest began to be seen at online auction sites for older microchips. Gallagher stated that it’s not just the CPUs themselves that people collect. Some individuals are collecting decades old software, books and user guides. The bottom line is that if it’s related to computers and was produced in the 1970s, the item will probably fetch a good price.

“Ebay is the No. 1 source for most collectors but amazingly enough some of my rarest chips came from scrap bins. They were only days away from being melted down for their gold,” said Gallagher. “There are also chip brokers online such as usbid.com that are just now becoming aware of what they have and who are already starting to increase their prices.”

Gallagher pointed out that as interest in vintage microchips has grown, dozens of websites focusing on the hobby have been set up. Most of the larger collectors have sites and a few of them have forums. As of yet there are no specialized conferences devoted to computer hardware of historical interest, although in Germany some computer shows have seminars on the topics.

“My website is set up to show off my collection and to encourage trading with other collectors. Most websites on this topic are extremely informative and can answer most any CPU question you could possibly have,” advised Gallagher. “One of my favorite sites/forums is cpu-world.com. The owner of this site collects every chip manufacturer known. I have met collectors on this forum who have been collecting for almost three decades!”

Still skeptical about the potential for CPU collecting? Think again. Even though Intel produced tens of thousands of early chips, most of them don’t exist anymore. Early chips were melted down to recover the gold in their component parts. The remaining ones are all dated and durable, both important aspects of any collectible.

While serious collectors in the West have been quietly gathering up vintage CPUs over the past few years, those collectors haven’t had access to the Middle East’s companies and computer dealers. Many of the machines imported into Saudi Arabia in the 1980s were stuffed into basement and roof storage areas as they were replaced by newer models in the 1990s. Even when they first appeared in the Kingdom, those early computers were often older models, no longer popular in Europe and the US. They are prime sources for 1970s microchips. And every city in Saudi Arabia has scrap and auction yards, which became dumping grounds for old computers.

“For those individuals ready to set off on a treasure hunt for rare and valuable microprocessors here’s a quick list,” said Gallagher. “C4004, C4040, 8080, C8080, MC8080, G8008, X8008, C8085 and C8086, all these go for at least $100 and some of them will go for over $1,000. Generally speaking anything from Intel with a date code from the 1970s is worth more than its gold value. Gold value for most ceramic computer chips is around $2 to $4.

That's not Junk. That's early Tech. (2005)

Gordon Bell

BusinessWeek, February 21, 2005

Prices for early computers and other geek memorabilia are on the rise.

Gordon Bell can hardly believe what he sees when he scrolls through the online catalog for a Feb. 23 (2005) Christie's auction of computer memorabilia in New York. "Oh my God, the prices!" exclaims the Microsoft senior researcher, a big-time collector of computer-related books, documents, and other artifacts, most of which he has donated to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif. One thing that catches his eye in the 355-item "Origins of Cyberspace" catalog is a first edition of a 1617 treatise by John Napier, the Scottish mathematician whose invention of logarithms was a key advance in creating the early calculators that evolved into today's computers. The auction house figures it will go for $25,000 to $35,000. "I paid $6,000 in 1982" for a similar copy, he recalls.

Bell isn't the only connoisseur in a tizzy over the rising cachet and prices of computer memorabilia. Whether 17th-century mathematics books, mid-1940s documents connected with pioneering executives, or the first 1970s-era microcomputers, prices have soared in recent years. Apple Computer's first model, an Apple 1 introduced in 1976 for $666, now typically fetches $16,000 to $20,000 if it's in good condition, says Sellam Ismail, a curator at the Computer History Museum. Christie's estimates the most expensive item in its sale, a 1946 business plan for the first modern computer company, Electronic Control Co. of Philadelphia, will sell for $50,000 to $70,000. The company, a predecessor to today's Unisys, became famous for its Univac computers. Electronic Control's founders, John Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, were part of the team that built the ENIAC, the first "large-scale general purpose electronic digital computer," according to the Christie's catalog. It weighed 30 tons and contained 18,000 vacuum tubes.

Part of the appeal of computer collectibles is there's something for everybody's budget. Indeed, the modern computer industry is so new that key items are still widely available and inexpensive. "If you just look into it a little, you can amass a very good collection," says manufacturing consultant George Keremedjiev, who in 1990 founded the American Computer Museum in Bozeman, Mont. For instance, a copy of the famous January, 1975, issue of Popular Electronics with a story on the Altair 8800, an early kit computer that helped inspire the founding of Microsoft, still goes for $100 to $175, notes Michael Nadeau, author of Collectible Microcomputers (Schiffer Books). Brochures for classic home computers such as the 1984 Commodore V364 can be found for $50 or less, he says, while Christie's figures "Brainiac," a 1966 "electric brain" kit designed by computing pioneer Edmund C. Berkeley, will sell for $800 to $1,200.

Most computer collectors are males with a background in engineering. A few major players have tried to document the entire history of computing, such as Bell, who was instrumental in the creation of Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC); Paul Pierce, a retired Intel (INTC) engineer in Portland, Ore.; and Keremedjiev. Others, such as Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, focus on specific periods. Not surprisingly, Allen's specialty is the history of microcomputing, and he is donating his collection to the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science for an exhibition space that will open in 2006.

On the Cheap

Small collectors tend to be tinkerers. They like to fiddle with old machines, swap parts, recover old software, and get the antiques up and running again. They also collect manuals, brochures, and company documents. The machines aren't really good for very much; the cheapest PC you can buy today has far more power. But the vintage equipment still attracts a following. Says Wai-Sun Chia, 38, a software engineer with Hewlett-Packard in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, who collects vintage DEC minicomputers: "The old machines are more interesting because they were made with boards rather than a single chip. It's like an antique car: You can go inside and figure out what each part does."

This type of collecting can be remarkably inexpensive. "The deal I've made with my wife is that my collection has to be self-supporting," says Jack Rubin, a suburban Chicago collector who funds new purchases by trading or selling one of his 50 or so computers. Classic microcomputers such as the Altair 8800, which originally retailed for about $400 as a kit and can now fetch up to $3,000, are getting pricey. But old minicomputers and mainframes can often be had for around $1,000. Patrick Finnegan, a systems administrator at Purdue University, recently paid $1,100 on eBay plus $200 for shipping for a vintage IBM mainframe that cost more than $1 million new. Storing the bulky old machines is often a collector's main expense: Pierce bought a warehouse to house his collection, considered the largest of its kind in the world outside a museum.

If this hobby appeals to you, it's not hard to get started. If you're mainly interested in historical documents, work with a reputable dealer, such as Uwe Breker in Cologne, Germany; John Kuenzig in Topsfield, Mass.; or Jeremy Norman, the Marin County (Calif.) author and dealer who built the collection Christie's is selling. The Web sites of the two U.S. computer museums and Germany's Heinz Nixdorf Museums Forum are also chock-full of historical information.

Some collectors spend a lot of time searching eBay and rummaging around at flea markets, thrift shops, and computer recycling centers. Two annual events are also invaluable, according to Keremedjiev: Hamvention, an annual ham-radio flea market in Dayton in late May that he says is "a gold mine of early technology," and the Vintage Computer Festival swapfest that Ismail puts on every November in Mountain View. Spin-off Vintage Computer Festivals organized by collectors are held in the Midwest, on the East Coast, and in Europe.

Study up before you buy. Seemingly inconsequential details can make all the difference in determining value. Aficionados know that a tan vintage Osborne portable is worth more than a gray one because the earlier tan models are much rarer, Keremedjiev says. When it comes to DEC's PDP-8 minicomputers, the very first ones (dubbed straight 8s) are worth $15,000 to $20,000, while later models fetch only between $800 and $3,000, Ismail says.

If you're careful, "this is a very good investment," Keremedjiev contends. Old machines are increasingly hard to find. And more people are becoming aware of the value of computer-related historical material. "I'm stunned," says Leonard Kleinrock, a University of California at Los Angeles computer science professor considered one of the founding fathers of the Internet, upon learning the value Christie's has put on some of his signed papers. It estimates a copy of his first book that he signed for Norman, a letter he sent the dealer five years ago, and other items could go to up to $3,500. In the past, Kleinrock says he never thought twice about sending his autograph to collectors who asked for it. Those days are probably as long gone as the IBM 709 mainframe.

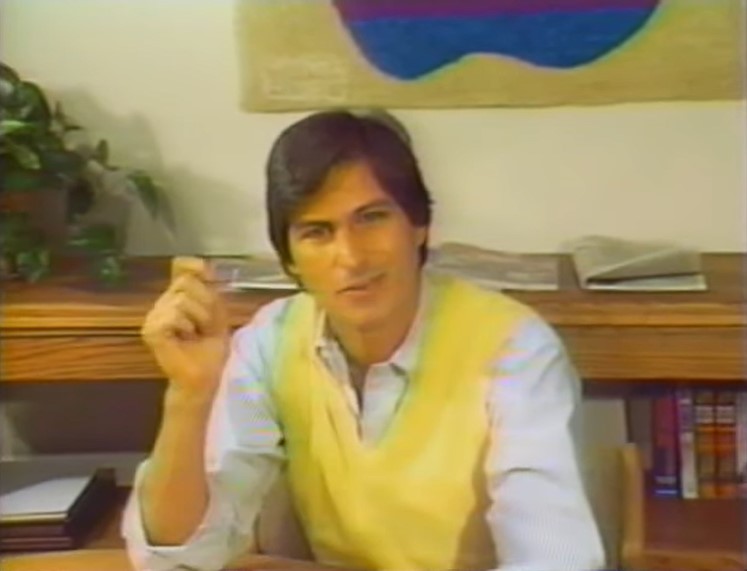

Yesterday's State of the Art is Now Regarded as "Artwork"

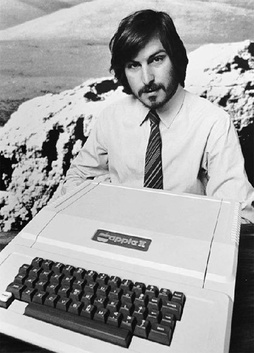

Steve jobs and his Apple II Computer (1977)

By Jose Antonio Vargas, Washington Post

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

The year was 1986 and Bud Ballos was an eighth-grader, a proud owner of a brand-new computer with what was to him "a weird thing" called a mouse.

Remember the Apple II? It was a fixture -- in the library, next to the card-catalog filing cabinet -- in many a middle school beginning in the 1980s.

"This was the start of the new computer, and at the time, I didn't really know what it was," Ballos says of his very first desktop, its screen no bigger than 7 inches by 5 inches, its color off-white, the kind of plastic that starts to yellow after a while. In the early years, not too many families actually had a computer at home. "I thought it was cool. My friends thought it was cool. We'd look at it and go, 'Wow, all right.' "

Ballos is 33 now and goes by Thomas rather than Bud. He's a novice collector and a random one at that: coins from the United States and Canada, belt plates from the Civil War, Native American spearheads and arrowheads, some of them 1,300 to 3,000 years old. They're all kept in the garage of his Ashburn home, where the showpiece -- "I did my homework on it; I played Donkey Kong on it; I brought it with me to college," he explains -- is his Apple IIc.

You'd think Ballos would have trashed or recycled his childhood Apple, but these days people are holding on to their first (and second, and third) desktops and laptops. Some keep them for nostalgia's sake, others for the kitsch value. Whatever the motivation, the urge to hang on has turned yesteryear's outmoded computers into today's historic artifacts -- giving them a growing value in the ever-so-hungry collectibles market.

From an early 1975 Altair 8800, named after a planet in a "Star Trek" episode, to a 1981 IBM Personal Computer that a young Bill Gates helped develop, what's on the collectibles menu covers a broadening taste. Some of these computers are rare. Some are actually quite common and may be sitting in people's basements right now.

Pepe Tozzo, author of the upcoming book "Retro Electro: Collecting Technology From Atari to Walkman," puts the price of the Altair, depending on its condition, between $930 and $2,785. But that's chump change compared with the $72,000 that Lot 238 -- the eight-page typed "Outline of Plans for Development of Electronic Computers," written in 1946 and regarded as the "founding document of the computer industry" -- brought at Christie's in New York in February.

Ten years ago, the mantra was that old computers were worthless -- smushed, forgotten, unbought in roadside yard sales. Today, the chances of scoring undiscovered gems at Sunday flea markets, or thrift shops on Nowhere Boulevard, or computer recycling centers on Faraway Street, are still pretty good, but even casual collectors spend a great deal of time shopping and researching online. There's Classic Tech and the Obsolete Technology Website, to name just two sites, and of course there's eBay, where on any given day dozens of vintage IBM, Atari, Amiga, Apple, Commodore, you name it, are up for bidding.

On a recent Wednesday, with 4 days 7 hours left on a listing, the top bid for an IMSAI 8080 microcomputer circa 1977 -- Matthew Broderick, in the 1983 film "War Games," almost started global thermonuclear war with one -- is $1,025. "I built it from kit and used for several years," writes the eBay seller. The bid started at $450.

Tony Romando, editor in chief of Sync, the men's magazine for the gadget-obsessed, says there's a one-word reason why people collect old hard- and software: cool.

"Who keeps an Apple II laying around? The hipster who owns a Treo cell and a PowerBook G4 and an iPod but last month went out and bought a rotary phone for his living room and sometimes walks around with a Walkman for street cred," says Romando. He keeps his circa-1999 iBook -- the one that looks like a toilet seat -- in the basement, next to one of those tiki lamps that repel mosquitoes. "Nobody's buying these old computers for the technology. They're buying it for style. For a lot of people it's artwork."

Sync runs a column in which a resident expert prices readers' electronic treasures. To Ritesh Dulal of Lexington, Ky., who wrote in asking about "a box full of Bell & Howell Apple II dinosaurs," Sync suggested that instead of cashing in for an estimated $300 ("with appropriate manuals"), he should hang on: "You never know when that Mac-crazed hottie from work is going to drop by for drinks. You'll score with this super-hip antique on your desk." Apart from the hipness factor, Michael Nadeau, author of "Collectible Microcomputers," a field guide of sorts for collectors, says holding on to a vintage computer is about taking a stroll down memory chip lane.

"If you grew up in the late '70s, for example, and you used this computer, the computer meant something to you," says Nadeau, who founded the Classic Tech site. He has a soft spot for Radio Shack TRS-80s, affectionately known as Trash 80s. "I think cars make for a good analogy: If you grew up in the '70s, the Corvettes, the Mustangs, the Camaros meant something to you. Maybe you didn't own one of those cars, but you wish you had."

For uber-collector Sellam Ismail, storing his more than 2,000 computers locked in a 4,500-square-foot warehouse in Livermore, Calif., is akin to storing history. If the warehouse weren't so messy, he says, he'd fit more. He owns Commodore 64s, one of the most popular computers of the 1980s; every member of the Apple II family; and a PDP-8, a rare creation from the now-defunct manufacturing giant Digital Equipment Corp.

"It's worth at least $20,000," he says of his PDP-8, considered by many to be the first "minicomputer" -- meaning it didn't fill an entire small room -- of the 1960s.

"Everything is happening so fast -- computers that are only 20 years old are completely outmoded, and even today computers that are only five years old are considered outdated, " says Ismail, a self-described "computer archivist" who seems to keep every detail of every computer ever built in memory, and that's not an exaggeration. In computer circles (read: lots of guys who studied engineering in college and cut their teeth on their first PCs and Apples), he's known as the proprietor of the world's largest collection of privately owned computers. He organizes the Vintage Computer Festival, an international Shangri-La for computer collectors and hobbyists. Now regularly held in Mountain View, Calif., in the fall, the festival started in 1997. Three years later, the first European festival was held in Munich, and the inaugural Midwest Vintage Computer Festival at Purdue University in Indiana will take place July 30.

For Ismail, another reason for collecting vintage computers is that computers back in the '60s, '70s and '80s -- the way they looked, the way they were built -- were much more interesting.

"Most of the PCs that have come up in the past 15 years, there's nothing special or interesting about them. It's the same box, no matter from what manufacturer," says Ismail. "What computer collectors tend to focus on are computers that are unique -- you get to play with architecture that's completely foreign from what you're used to."

For this reason and others, the Holy Grail of any serious collector is the first in the Apple line, the Apple I, which was designed by the Steves -- Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak -- and sold in 1976 for the superstitious price tag of $666.66. It even has its own fan club; the Apple I Owners Club was born in 1977, the same year production of Apple I's was discontinued.

"There were 200 made in total," says Ismail. "I've tracked down 35 so far."

In the past five years, during the festival in Mountain View, Apple I's have been up for bidding three times. One sold for $16,000 in 2003, Ismail says, and to his chagrin, he doesn't own one.

The Apple IIc (the "c," by the way, stood for "compact") is not as scarce as the Apple I -- some 400,000 were produced the first year it came out. But tinkering around with his Apple, a gift from Mom and Dad, is always a good time, says Ballos. He shows it off to people; for a while, his 12-year-old son, Colby, played with it.

Ballos, who works in sales for Covad Communications, an Internet company, owns three modern computers: two Shuttle XPCs and a Dell laptop. If he sold his Apple IIc, he'd include the original manuals, and give away the games -- Flight Simulator; Mickey's Space Adventure; One-on-One, a basketball match that pits Julius Erving against Larry Bird -- that are on 5 1/4 -inch floppies, from when a floppy was still floppy.

How much would his Apple sell for? He isn't sure. Ismail estimates no more than $300, if Ballos has all the original materials; author Nadeau puts it at a more modest $200.

For now, it seems, the Apple IIc that Ballos got for Christmas in 1986 is still a tad too young to be worth real money.

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

The year was 1986 and Bud Ballos was an eighth-grader, a proud owner of a brand-new computer with what was to him "a weird thing" called a mouse.

Remember the Apple II? It was a fixture -- in the library, next to the card-catalog filing cabinet -- in many a middle school beginning in the 1980s.

"This was the start of the new computer, and at the time, I didn't really know what it was," Ballos says of his very first desktop, its screen no bigger than 7 inches by 5 inches, its color off-white, the kind of plastic that starts to yellow after a while. In the early years, not too many families actually had a computer at home. "I thought it was cool. My friends thought it was cool. We'd look at it and go, 'Wow, all right.' "

Ballos is 33 now and goes by Thomas rather than Bud. He's a novice collector and a random one at that: coins from the United States and Canada, belt plates from the Civil War, Native American spearheads and arrowheads, some of them 1,300 to 3,000 years old. They're all kept in the garage of his Ashburn home, where the showpiece -- "I did my homework on it; I played Donkey Kong on it; I brought it with me to college," he explains -- is his Apple IIc.

You'd think Ballos would have trashed or recycled his childhood Apple, but these days people are holding on to their first (and second, and third) desktops and laptops. Some keep them for nostalgia's sake, others for the kitsch value. Whatever the motivation, the urge to hang on has turned yesteryear's outmoded computers into today's historic artifacts -- giving them a growing value in the ever-so-hungry collectibles market.

From an early 1975 Altair 8800, named after a planet in a "Star Trek" episode, to a 1981 IBM Personal Computer that a young Bill Gates helped develop, what's on the collectibles menu covers a broadening taste. Some of these computers are rare. Some are actually quite common and may be sitting in people's basements right now.

Pepe Tozzo, author of the upcoming book "Retro Electro: Collecting Technology From Atari to Walkman," puts the price of the Altair, depending on its condition, between $930 and $2,785. But that's chump change compared with the $72,000 that Lot 238 -- the eight-page typed "Outline of Plans for Development of Electronic Computers," written in 1946 and regarded as the "founding document of the computer industry" -- brought at Christie's in New York in February.

Ten years ago, the mantra was that old computers were worthless -- smushed, forgotten, unbought in roadside yard sales. Today, the chances of scoring undiscovered gems at Sunday flea markets, or thrift shops on Nowhere Boulevard, or computer recycling centers on Faraway Street, are still pretty good, but even casual collectors spend a great deal of time shopping and researching online. There's Classic Tech and the Obsolete Technology Website, to name just two sites, and of course there's eBay, where on any given day dozens of vintage IBM, Atari, Amiga, Apple, Commodore, you name it, are up for bidding.

On a recent Wednesday, with 4 days 7 hours left on a listing, the top bid for an IMSAI 8080 microcomputer circa 1977 -- Matthew Broderick, in the 1983 film "War Games," almost started global thermonuclear war with one -- is $1,025. "I built it from kit and used for several years," writes the eBay seller. The bid started at $450.

Tony Romando, editor in chief of Sync, the men's magazine for the gadget-obsessed, says there's a one-word reason why people collect old hard- and software: cool.

"Who keeps an Apple II laying around? The hipster who owns a Treo cell and a PowerBook G4 and an iPod but last month went out and bought a rotary phone for his living room and sometimes walks around with a Walkman for street cred," says Romando. He keeps his circa-1999 iBook -- the one that looks like a toilet seat -- in the basement, next to one of those tiki lamps that repel mosquitoes. "Nobody's buying these old computers for the technology. They're buying it for style. For a lot of people it's artwork."

Sync runs a column in which a resident expert prices readers' electronic treasures. To Ritesh Dulal of Lexington, Ky., who wrote in asking about "a box full of Bell & Howell Apple II dinosaurs," Sync suggested that instead of cashing in for an estimated $300 ("with appropriate manuals"), he should hang on: "You never know when that Mac-crazed hottie from work is going to drop by for drinks. You'll score with this super-hip antique on your desk." Apart from the hipness factor, Michael Nadeau, author of "Collectible Microcomputers," a field guide of sorts for collectors, says holding on to a vintage computer is about taking a stroll down memory chip lane.

"If you grew up in the late '70s, for example, and you used this computer, the computer meant something to you," says Nadeau, who founded the Classic Tech site. He has a soft spot for Radio Shack TRS-80s, affectionately known as Trash 80s. "I think cars make for a good analogy: If you grew up in the '70s, the Corvettes, the Mustangs, the Camaros meant something to you. Maybe you didn't own one of those cars, but you wish you had."

For uber-collector Sellam Ismail, storing his more than 2,000 computers locked in a 4,500-square-foot warehouse in Livermore, Calif., is akin to storing history. If the warehouse weren't so messy, he says, he'd fit more. He owns Commodore 64s, one of the most popular computers of the 1980s; every member of the Apple II family; and a PDP-8, a rare creation from the now-defunct manufacturing giant Digital Equipment Corp.

"It's worth at least $20,000," he says of his PDP-8, considered by many to be the first "minicomputer" -- meaning it didn't fill an entire small room -- of the 1960s.